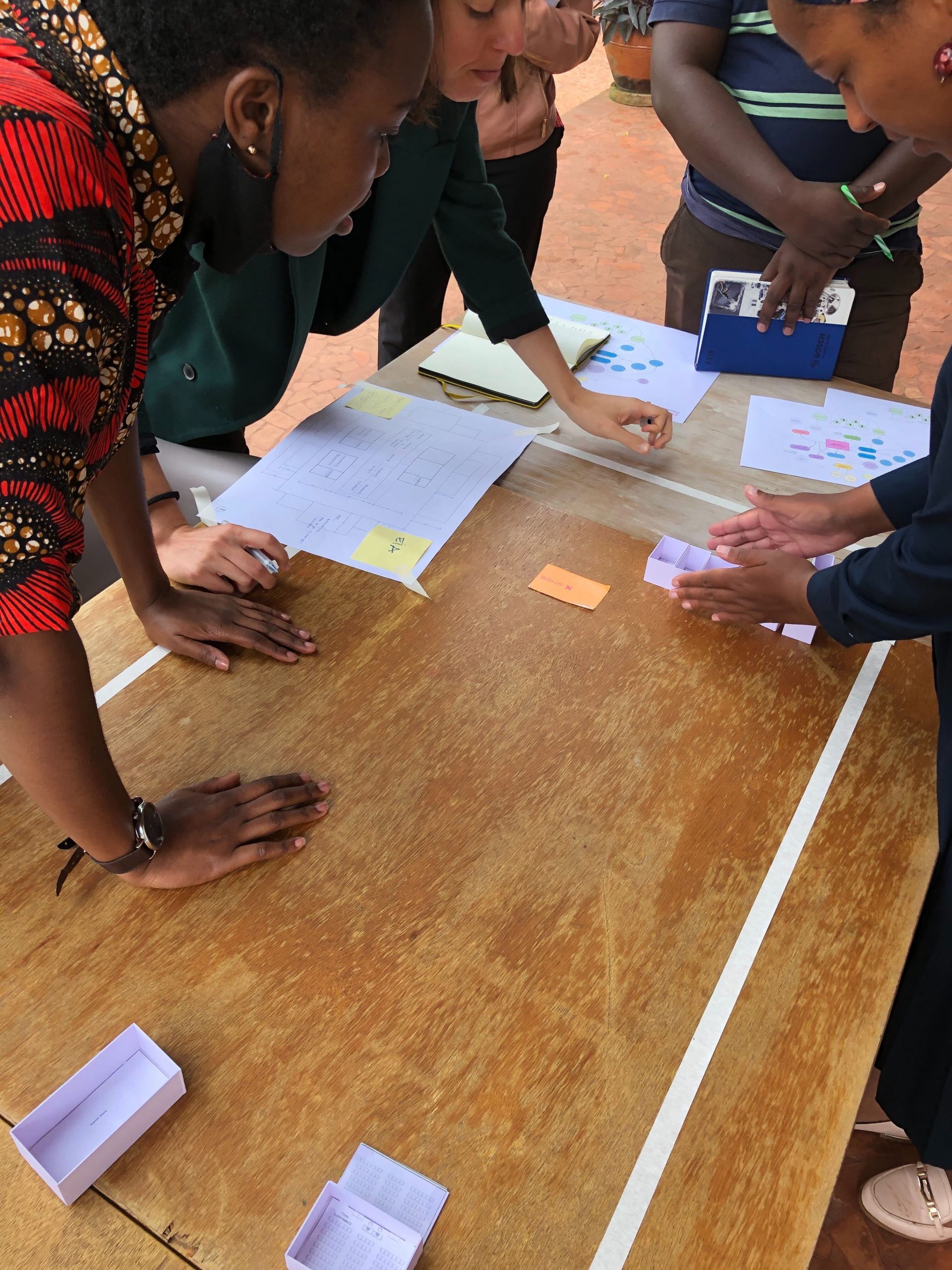

In 2013 whilst running the construction of a children’s home in Nakuru, Kenya, a local woman, Hellen (pictured below, centre), showed up at our site gate asking for work. Hellen joined our work site the very next day, shortly seeing to it that a further dozen more women were enrolled to our workforce as well.

The remarkable impact they had on productivity, quality and team culture ultimately proved the inspiration behind Buildher, the organisation I co-founded in 2018 to train disadvantaged women in construction and life skills.

Yet in my work today, leading BuildX on a mission to make net zero carbon buildings the norm, I look back on the impact that now hundreds of incredible women have made on our projects and notice something I missed. Women also wasted less building material.

This may not seem a major omission until you recognise that on average 30% of the total volume of all material transported to construction sites ends up as waste. Worse still, at a time when globally we need to be taking urgent action to eliminate global carbon emissions, of which buildings and construction are responsible for a staggering 39%.

So if we are to have any hope of mitigating climate change I believe we must start by urgently addressing the lack of women in the building industry. According to a Women in Real Estate (WIRE) Kenya survey, women currently account for a mere 11.8% of all registered architects in Kenya, 15.45% of contractors, and an even more dismal 7.3% of engineers. It’s even rarer to find women in skilled artisanal roles on site.

BuildX now employs at least 30% women construction teams, often as high as 50%, and to put it simply I see better, less wasteful practices than when we employ men only. A simple illustration of this is the humble mortar pan – the vessel used by masons to hold wet mortar whilst they lay a stone wall. At the end of each work day, time and again, I find women masons laying the last of their mortar just as closing time arrives. Contrastingly, their male counterparts can often be seen discarding a recently batched mix into the foundations or hurriedly rushing to use it up at the expense of their quality of work.

In Kenya, the need to change our building habits at all levels is especially pronounced. Construction practices continue to rely heavily on high carbon emitting materials such as concrete and steel. This is not uncommon in much of the world, yet here these materials are more entrenched in social aspiration. So much so that any alternatives struggle to get noticed.

To reduce the embodied carbon footprint of these buildings – meaning to minimise the impact of the materials and methods used to build – there are broadly-speaking two approaches we can take. We can strive to use less quantity of material, whether by shrinking the volume of walls, floors, columns or beams or by reducing the proportion of any of the “bad stuff”, like cement. Off-site prefabrication of building components can also offer greater control and thus less waste.

The other approach is to substitute materials that cause harm for more environmentally-friendly options. In particular, the use of renewable natural materials such as timber which can now be engineered to produce remarkably strong and durable net zero carbon structures using sustainably managed wood. Use both approaches together – reduction and substitution – and we can truly begin to meet our targets.

We have long known how to build sustainably but progress in the real world remains slow, in part because it requires not just technical solutions but also a willingness to alter our behaviours for any substantial change to occur. Studies show that women, over men, have greater capacity for change and greater propensity to manage resources more sustainably. For clients, developers and construction companies employing gender-balanced teams this brings commercial advantages through hard cost savings as well as just environmental gains.

Women are also the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. With 70% of all women living in poverty, they are disproportionately affected by extreme weather events, loss of agricultural productivity, destruction of life and property and so on, all of which stem from the climate crisis.

In any industry, we surely know by now that diverse teams solve problems more effectively and come up with greater innovation and more successful solutions. Moreover, increasing research into human-centred design (and design thinking) suggests that groups which include people suffering from the problem being addressed outperform others, no matter how diverse or how much effort is taken to empathise with the beneficiary audience.

Thus, to give ourselves the best chance of addressing climate change and eliminating carbon emissions in buildings and construction, we must urgently involve those most directly affected and ensure diversity – which includes women as representatives of over half our human population – in our pursuit of this change.